Resilience Unbound on the Silk Road Mountain Race

We face a few challenges in life that push us to face our fears — to our absolute limit.

It’s those moments that transform us — moments that break us and make us dig so deep within ourselves to find that something that we never thought existed. These are the experiences that help us learn and grow.

The Silk Road Mountain Race is definitely one such challenge. The sleepless nights, the euphoric feelings, the conscious decision to continue and to suffer through the heat and cold — day and night in the endless Tian Shan mountains. You try to recover and regain the strength, pushing forward only to sink deeper at the end of the day — you struggle to stay awake and do it over and over, hoping to get to Cholpon Ata.

Eat, ride, sleep, repeat ... this is my journey called The Silk Road Mountain Race.

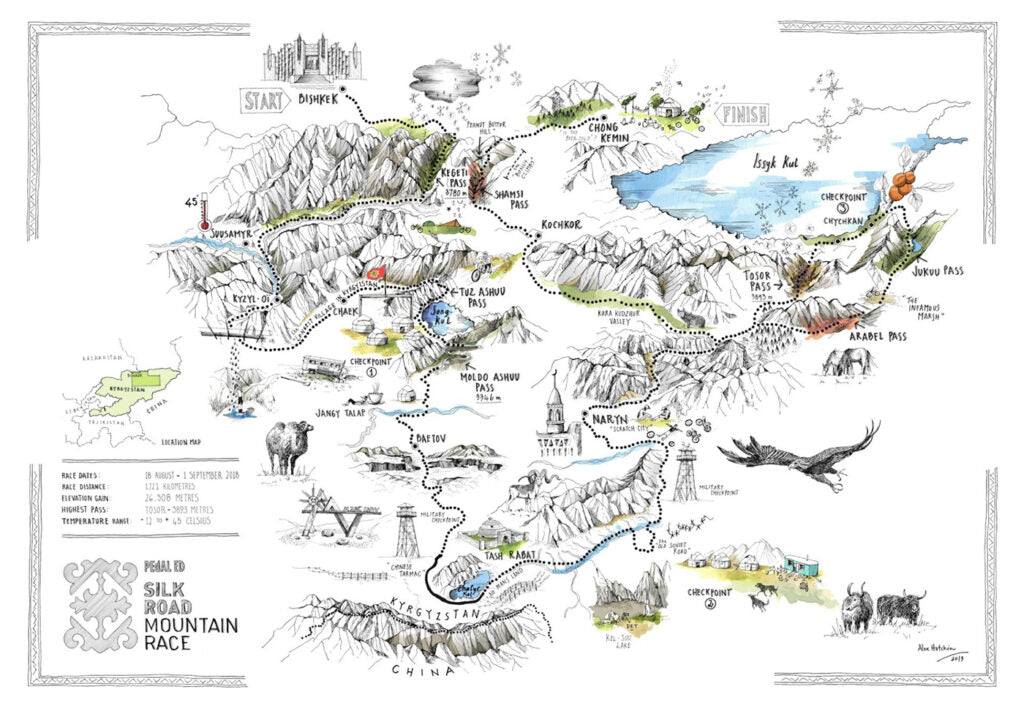

Silk Road Mountain Race 2019 - Race Map Illustration by Alex Hotchin

Silk Road Mountain Race 2019 - Race Map Illustration by Alex Hotchin

THE SILK ROAD MOUNTAIN RACE AT A GLANCE:

- Silk Road Mountain Race 2019 route

- 1708 km (1061 miles) with 28,000 m (92,000 ft) of the climbing

- The equivalent of climbing Mount Everest over 3 times

Kyrgyzstan is an incredibly beautiful country in Central Asia and has the perfect setting for an epic adventure. Massive mountains, vast grasslands, high alpine valleys, stunning wildlife, and rugged terrain make it a perfect playground for an incredible bike race. Being solo and unsupported while being far away from civilization tucked into the remote Tian Shan mountains makes SRMR live up to its title for the world’s toughest mountain bike race.

Credit: SRMR Photographers

Credit: SRMR Photographers

I have completed several long-distance, self-supported bike-packing races in the past, but Silk Road Mountain Race would be my first solo, unsupported race in the mountains.

I was already planning a long bike packing expedition from India to Germany that I call Freedom Seat when I applied for SRMR 2019. For Freedom Seat, I rode a tandem bike from India to Germany and picked up random strangers along my way to help raise awareness and funds for the victims of bonded labor slavery. I felt that if I could survive the Freedom Seat India-Germany expedition, I would have just enough time to train and get ready for SRMR.

Some Pre-Race Adventures

While boarding my flight to Kyrgyzstan from New Zealand, the airline refused to let me board, stating I didn’t have an e-visa. I was clearly showing the document from the Kyrgyzstan Ministry of Foreign Affairs stating that my visa had been approved and that I could collect my visa at the airport in Bishkek. Unfortunately, the letter was in Kyrgyz and the airline said that I was at high risk for getting my transit visa denied since I would be transiting through multiple Chinese cities.

The airline didn’t offer me any alternative besides denying me from boarding the plane and told me I would have to look for tickets to fly through some other airline. My dream of racing SRMR was going to be over before it started.

I asked the airline if they would let me board if I could get the letter translated and they kind of agreed. I had to download 15+ apps to parse the photo of the approval letter and use Optical Character Recognition to translate it from Kyrgyz to English. Of the 15 apps, only one app did the job. Finally, the airline agreed to let me board provided that I sign a waiver saying I’m fully responsible if my transit visa falls through.

Silk Road Mountain Race is the toughest mountain bike race in the world — but even getting to the start line became a huge adventure. All said and done, the immigration through China and my entry to Kyrgyzstan went well and I was given a visa without any issues.

Credit: SRMR Photographers

Credit: SRMR Photographers

Calm Before the Storm

Having arrived in Kyrgyzstan just 3 days before the race, I didn’t have much time to acclimatize for the race but I did have a great time meeting other riders at the pre-race dinner party. Several riders had arrived weeks prior to the race and were training hard on the course.

I tried my best to not talk about the race prep with other riders during the race registration day. My ambitious goal was to complete the race in 10 days or under — but my ultimate goal was just to make it to all three checkpoints within the cut-off and complete the race within the 15-day time limit.

I packed up my bike with everything I needed for the next 15 days and tried to get some rest but sleep wasn’t in the cards. Anxiety kicked in and made me wonder what’s waiting out there ... especially with weather warnings for snow and rainfall at high altitude. It was about to get rugged.

Journey to Check Point 1

Race day morning was just perfect. 135 riders were poised to face the 2019 edition of SRMR. We all rode quietly from Bishkek to the big flag pole up the hill in Orto-say. Everyone toed the start line to start riding the 1708 km with 28,000 m elevation to compete in the SRMR. It had begun. The riders were finding their groove and the line started thinning out. I found a comfortable pace and my goal for the day was to get over Kegety Pass at 12500 ft.

Credit: SRMR Photographers

Credit: SRMR Photographers

It was a great start with beautiful weather at 9 a.m. but as we started approaching Kegety Pass it immediately turned into rain and snow. Soon the sun went down and the temperatures plummet to the lower 20s. I kept pushing to get over the pass and eventually did.

After descending Kegety Pass, it was way too cold to continue and I decided to set up my camp — it was 4 a.m. Sun, wind, rain, and snow all within a 12-hour period — the race was off to a great start. I woke up to a completely frozen tent but had a good 3-hour rest. I reached out for my water bottle to find that it was completely frozen solid. With no sun in sight to warm up, I decided to pack up and push my bike along the steep slope hoping that would warm me up.

Yet another big pass in Karakol Valley and then down to Kojomkul where there was a village to resupply. I slept along the field for the night and had a good rest to tackle the climb in the morning to Song Kul Lake. The route to Song Kul lake via Tux Ashuu was so deceptive. I thought I was at the lake level, but there were several steep sections that were relentless. Song Kul Lake is absolutely stunning but my eyes were set on the yurt camp that was the race’s first checkpoint. It started to hail and turned into a thunderstorm just as I reached the checkpoint — 2 Days, 5 Hours, and 15 Minutes.

Checkpoint 1 to Checkpoint 2: 220 miles, 13,200 ft ascent, and 12,100 ft descent

Checkpoint 1 served us all a delicious hot meal and some hot tea. After getting my brevet card stamped, I hit the road again. The road skirted around Chatyr Kul Lake and then dumped into a steep descent with crazy switchbacks towards Baetov. The descent was sketchy at places and the rocky gravel terrain didn’t help with traction. Seeing the smooth tarmac that eventually followed was such a sweet thing to my sore eyes and my even more sore butt.

I hammered it down to Baetov, resupplied at a local village shop, and headed to a guest house where several riders were spending the night. No flushing toilet — just a hole in the floor. The shower was luke-warm so I decided to skip the shower and crashed on a mattress on the floor. The climb out of Baetov was just stunning, but this section was also pretty rugged and remote.

CP2 sits on the border next to China and needs a border permit. While getting the border permit checked at Torugart, I asked the officer for water. One of the friendly ones grabbed our bottles and borrowed a bike and headed towards his camp. The other officer offered a bottle of liquid that appeared to be milk. The first taste of it almost made me throw up. He said it was horse's milk and that it was good for your health. I didn’t want to appear rude and gave it back, thanking him with a smile.

Credit: SRMR Photographers

Credit: SRMR Photographers

The temperature plummeted again and forced me to pitch a tent by the side of the road, next to a river bed along a cliff that offered sufficient protection from the wind. I had an early start the next day. The route had several river crossings, but the road heading towards CP2 was the most picturesque in my opinion — views so breathtaking that I stopped every mile to take it all in and snap some photos.

I made it CP2 and got my brevet card stamped. It was time to fix my gears and sew my rainproof pants that tore where they got stuck on the chainring. It was very tempting to stay the night at the warm yurt. Instead, I decided to push on and made it CP2 well ahead of the cutoff — 4 Days, 9 Hours, and 15 Minutes.

Credit: SRMR Photographers

Credit: SRMR Photographers

Checkpoint 3 Bound

I had no idea what I was getting into until I got to the bottom of the old soviet road. I had to stop and triple check my map to make sure I was following the course. It was the steepest section that I had ever climbed with my bike in my entire life. It was so steep that you had to take a break after every 5 steps, with a 14-18% inclination the entire way. The section is also infested with old rusty barbed wire and navigating through this section at night was extremely sketchy. The only good thing about doing this at night was that you don’t really see how steep it truly was.

With my head down and arms holding the handlebar, it was a death march — one step at a time. Soon it transitioned into an amazing single track and riding down the track in moonlight all by myself was an amazing experience. When I reached the bottom of the hill, I set up my tent and got some rest before heading to Naryn.

The washboard road sections were making my bottoms so sore. The vibration makes your whole body shiver. Finding a smooth section at the very edge of the road was so tricky. Naryn is a big town with several resupply options but it was also an easy option to just turn back. I didn’t want to have any temptation. I had a big meal, lots of ice cream, loaded up my bags and hit the road as soon as possible. Some riders decided to quit and were making their bus reservations back to Bishkek. I rode until midnight and called it a day — pitched my Hornet™ along the river and went to sleep.

This section was both beautiful and enjoyable to rideable, but the weather went south pretty quickly and local Kyrgyz nomads took me under their wings. They filled my tummy with some delicious noodle soup, bread, and all the hot tea I could drink.

This experience showed me that language is never a barrier to human connection.

Leaving the comfort of the warm yurt and even warmer hospitality to head into the cold rain was extremely difficult. I waved to my hosts and headed into the storm. Soon the section turned into a mud bath. The peanut butter mud was so thick that I had to stop every quarter mile to wipe off the mud that was getting built up — it was practically everywhere.

I pushed on through the crazy rainstorm while descending numerous steep sections of gravel roads that were slick with peanut butter mud. I was covered in mud from head to toe but finally made it to CP3 — 7 Days, 9 Hours, and 46 minutes.

Last Big Pass

I was pretty happy to make it to all of the checkpoints well ahead of the designated cutoff. I just had to ride to the finish line and there was plenty of time to finish. I checked into a guest house along the shores of Issyk-Kul, had my first shower in 7 days. and after a hearty meal ... slept in a proper bed for the first time.

I was rolling towards Tosor town when I heard a loud pop and noticed that I had my first flat. It was pretty bad. There was a big hole in the tire and I had to fix it with a couple of patch kits. It all appeared normal but as I started heading towards Ton Pass and grained some elevation, the tire eventually became completely herniated and started rubbing on the fork.

Credit: SRMR Photographers

Credit: SRMR Photographers

I had another late night crossing ahead of me and getting over Ton Pass in snow and hail was so tough. The ridgeline was extremely narrow and icy — by far the sketchiest crossing of the Silk Road for me. The terrain was rocky and impossible to descend at night in total darkness. I pitched my tent just before a river crossing and decided to tackle it after sunrise.

It was a long ride towards the intersection cafe and the tire was getting worse. There was big gash by now and the tube was protruding through the tiny holes. I made it to the intersection cafe junction. After a good meal and restocking for the next section, I crashed on the floor of a tiny guest house.

Now, it was time to tackle Shamsi Pass. It was a horse trail and one of the most technical sections of the race — nearly a 20 km hike & bike section. The descent was even more gnarly and I was pretty much forced to push the bike all the way down until it became rideable. This section also had four river crossings and some of them were waist-deep. When an ominous-looking thunderstorm appeared in the distance, I decided to call it a night and slept along the side of the road. Two other riders joined me shortly after.

Bonus Climb and Peanut Butter Climb:

The three bonus hills after Shamsi were brutal as well. Especially the first one that had a solid 1000m steep climb. After hitting the highway, I stopped at Shabdan for a hot meal and rode to Chong Sary-Oy to restock, and then rode until 11 p.m. and pitched my tent along the side of the road. It was another night of good sleep — hopefully the last night outside.

I started the day early. Some friendly Kyrgyz nomads helped with breakfast and by now I started to like horse milk and cheese. Beggars can’t be choosers, I guess. Onward, I coasted to the bottom of the hill before the last climb of the course — Kok- Airyk Pass.

Credit: SRMR Photographers

Credit: SRMR Photographers

I met the Race Director, Nelson, at the top of the hill. As much as I was pissed at him during all those rough climbs and icy cold river crossings, I was equally appreciative of his effort to put together a race like this. It’s opportunities like these that make you dig deep and find a new level of resilience in yourself that you never thought existed. I thought the climb was hard but the descent was even harder — another steep section filled with landslide rocks strewn with some large boulders. You had to carry the bike on your shoulder to navigate through this landslide section.

Mountainside MacGyvering

Just after crossing Kok-Airyk Pass, the terrain became extremely rugged. The path was decimated with dozens of landslides with razor-sharp rocks and boulders. As I was cruising down very cautiously, a super-sharp rock edge pierced right through the tire and caused a flat and destroyed my tire.

Getting a split in the sidewall of your tire is a common problem. I have had dime-sized splits on the sidewall before that I was able to fix with a $5 New Zealand bill which is made out of plastic — but this one was worse. The sidewall was torn. A full-blown, long split caused by a sharp rock edge that actually ripped the tire. It left a sizable gash along the sidewall causing the inner tube to bulge out. I shouted! I cried! But I knew I had enough time to push the bike and finish before the cut-off.

What should have been a 2-hour ride was turning into a 10-hour death march to the finish line, but I was hell bound to finish no matter what.

After fixing the flat I needed something to boot the tire. I checked my bag and found my flowfold wallet. It’s made with recycled sails and it’s extremely tough. I emptied the contents of the wallet and booted the tire ... and it worked.

I was able to cruise downhill on some very rocky terrain — I prayed so hard the entire time. I told God that I would come to church every Sunday if he would take me to the finish line without any more damage to the tire. As soon as I reached the highway, I lay my head on the handlebar in relief. The wallet fix worked! And now it was just smooth asphalt all the way to the finish line in Cholpon-Ata — just 24 km left.

I was hit with a torrent of emotions and I rolled to the finish line. 12 days, 13 hours, and 30 minutes. After getting my final brevet stamped someone asked me what would I like to have. I said, “All I care for is a cold beer and some clean underwear."

I rode the entire race wearing the same pair of clothes and showered only once during the duration of the race. Shower and sleep never felt this good. This race taught me the real meaning of resilience. No matter how many times life punched me in the face, I had to recover, pull myself together, and keep moving.

A good night's rest is very critical in a race like this to sustain the daily mileage. Weight is also a critical part of your gear kit, as the challenge involves 92,000 ft of climb. A huge thanks to my sponsor, NEMO for recommending the best lightweight and most rugged sleep and shelter system I've ever used.

Credit: SRMR Photographers

Credit: SRMR Photographers

Gear List:

- Kayu™ 15° Men’s down mummy bag

- Tensor™ Insulated sleeping pad

-

Hornet™ Ultralight backpacking tent with Hornet™ Footprint

Naresh Kamur is an ultra runner and social activist who started Freedom Seat, a series of long-distance tandem bike expeditions to raise funds and awareness to end sex trafficking and bonded slavery and has been awarded the Wilderness Outdoor Hero of the Year runner-up for this project.